|

Another global first for Edmonton

By Michael O'Toole

Photos By: Ellis Brother Photography

Artificial intelligence

may still be widely viewed as the yolky domain of eggheads, spindly

academics bent on establishing that angels can indeed dance on pins.

Nevertheless, as with so

many other latent conveniences in life, most of us rely on this

often invisible task facilitator everyday, but seldom have the grace

to say thank you. This is particularly regrettable when we consider

that AI is perhaps the one algorithm that might actually have the

wits to appreciate the gesture.

“The exciting thing is

that artificial intelligence is real,” declares Dr. Russ Greiner

from the University of Alberta’s AI research unit—a man whose mild

resentment of the egghead label does not prevent him from

fraternizing forgivingly with representatives of his own species.

“People are making money from it. It’s not just an academic exercise

or a frivolity. Part of our mandate is to get business interested in

what we’re doing.”

Greiner’s speciality of

machine learning is itself a vast, seemingly limitless sub-category

of AI predicated on the effort to detect patterns and make decisions

based on those patterns. “Organizations that employ artificial

intelligentsia—machine learning (ML) people—to solve problems do so

because there’s no other technology that works for these problems,”

Greiner asserts.

It seems there are three

main situations where this typically holds good: 1) when nobody

knows the answer; 2) when people know the answer but can’t

articulate it; and 3) when the answer may be known and easy to

articulate, but it’s just too cumbersome to keep redoing the task.

Spam filtering is a choice candidate in the last category, while

healthcare, a key focus of Greiner’s research efforts, is a major

potential beneficiary in the first scenario.

“What genes are

associated with this disease? The way ML approaches this is to build

a classifier. You give me lots of data. Give me 100 patients who’ve

been at the same hospital… 50 patients have the disease and 50

don’t. Tell me their name, age, gender, smoking history, maybe their

genotype. Then I’ll find patterns, or my algorithms will find

patterns.”

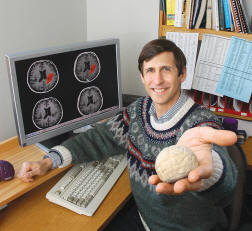

| Greiner’s

algorithms, with the help of the Alberta Ingenuity Centre for

Machine Learning are currently partnering with the Cross

Cancer Centre in Edmonton, divining patterns that will

identify patients who should respond well to a certain form of

treatment. The research is wide ranging and, in some respects,

groundbreaking. “My team has built the world’s best analyzer

of brain tumors—the world’s best, right here. This is a

project that people at MIT and McGill have tried to solve, and

we solved it by using machine learning techniques. And that’s

real data, real concerns, real interests—a project which makes

a difference.” |

|

Beyond medical science,

the pattern-finding capability of ML—and its AI cousins —makes it a

key component of credit card security, e-commerce, delivery routing,

load level prediction in the energy industry and a whole array of

business applications that fall mostly under the umbrella of

business intelligence. Internet search applications alone are

legion.

So who should be talking

to Greiner and his colleagues?

“Anybody who has data.

Try to find me a business sector that doesn’t have a gigabyte or two

sitting around and problems to solve. We’re trying to get people

excited about this. In fact, we are already an international player.

We have collaborations around the world. Edmonton’s been a harder

sell. It’s frustrating for me because we’ve got such a great answer

and there are so many applications that can use it.”

An Edmontonian long

since sold on the proposition is Celcorp’s founder and chief

technology officer, Bruce Matichuk, one of the region’s most vocal

and prolific champions of artificial intelligence and its power to

leverage business operations. His own company, which specializes in

systems integration, is already a veteran exploiter of the

technology.

Donning his industry

cheerleader hat, though, Matichuk turns to the more mall-friendly

realm of video games. “If you look at revenue worldwide, currently

the pc games industry alone makes more than Hollywood, so it’s

absolutely gargantuan and doubling in size regularly. At the core of

many of these games are things called AI engines.” These, Matichuk

expands, are all of the code and algorithms that make you, the

player, think that you’re interacting with another person—a

character that is actually using reasoning to decide what its next

best move is.

Encouragingly, Edmonton

is by no means a passive observer in this massive playpen. Sponsored

by the Alberta Ingenuity Fund, the University of Alberta proudly

sports an electronic entertainment and games research centre

described by Greiner as the strongest in the world. “We’ve

contributed ideas to Electronic Arts to help them debug their

programs by using our technology,” says Greiner. “That’s been very

effectively used.”

Also a key partner is

the high profile Edmonton games producer BioWare, which is currently

harnessing the power of AI in world class products like Baldur’s

Gate.

So much for the

software. What about technology you can really roll around in the

mud with? Michael Bowling, another jovial star of the U of A’s AI

research hub, is proud to represent robots of all shapes,

personality types and political leanings. As if they can’t speak for

themselves.

“There certainly is a

fairly heavy industry associated with robotics,” Bowling points out,

“but artificial intelligence in robotics is still fairly

undeveloped, so it’s unclear what the market looks like yet. One of

the things I’m interested in is to push the intelligence and

understanding of our world enough that we can start deploying robots

in more situations where it wouldn’t be cost effective to have a

human monitor it.”

|

With

this in mind, Bowling is currently involved in geo caching

research that requires a mobile robot to find a hidden object

by using GPS coordinates and its own precocious talent for

acquiring street savvy. “How do we build a map of our

environment, especially an unstructured environment?” Bowling

posits. “There has been a lot of research on how to do this

inside of buildings. But now, try to take that same technology

and move it outdoors. It doesn’t quite work so well. With its

sensors, it has to figure out that this is drivable terrain,

this is not, or maybe this is risky and if I can’t figure out

any other way to go then maybe I should drive over

this.” |

Among the future

applications of AI robotic technology, Bowling sees huge potential

within the oil and gas industries, where it currently makes no

financial sense to send humans to carry out inspections of

facilities on a regular basis.

In common with other

areas of artificial intelligence, though, entertainment appears to

be the motor zone. The latest incarnation of Sony’s celebrated AIBO

Dog can recognize a 1700-word vocabulary and incorporates learning

techniques to mimic canine behaviour so you can watch your robotic

dog ‘grow up’. The dogs are among several robot types that regularly

compete in the four separate AI soccer leagues at the U of A—all,

despite the chuckles of onlookers, as a testbed for various sober,

practical applications of the underlying technology. While Sony is

turning its attentions elsewhere, Bowling will continue improving

AIBO hardware to solve general problems.

“The reason AI in

robotics is not as big as I think it will be in future is that

robots are still a little bit expensive,” Bowling concludes. “As the

price of robots goes down, that will change.”

Within the artificial

intelligence industry as a whole, image problems linger. “AI as a

field has made some huge blunders over the last several decades,”

Greiner reflects ruefully. “We’ve had, unfortunately, some

charlatans, which makes everyone call into question anything we

say.”

Matichuk shares the

concerns about public perceptions, also finding irony in the fact

that as soon as the technology actually becomes useful, people don’t

think of it as artificial intelligence any more. Though this

societal mindset can be a hindrance from a marketing perspective,

Matichuk takes heart in observing, just a little quirkily, that

“these algorithms are finally getting out of the research labs and

into products that people are using every day.”

|